A Theology of the Generations: Do People Today Still Risk Feudalism in the Family? -- By: Beulah Wood

Journal: Priscilla Papers

Volume: PP 23:3 (Summer 2009)

Article: A Theology of the Generations: Do People Today Still Risk Feudalism in the Family?

Author: Beulah Wood

PP 23:3 (Summer 2008) p. 19

A Theology of the Generations:

Do People Today Still Risk Feudalism in the Family?

BEULAH WOOD, a New Zealander, has worked for extended intervals in India, Nepal, and Bangladesh since 1968. She now lectures and writes at the South Asia Institute of Advanced Christian Studies, Bangalore, South India. As a mother and grandmother, she longs for people to reach a gospel understanding of family life.

I am teaching an interactive class on family in a theological college in South Asia. Mothi Mary has organized her group to act as a mother, son, and daughter at the table. Daughter asks for a second helping. Mother says, “No. You do not need it.” Son asks for more. Mother gives him extra food. The children are leaving for school. Mother gives son a cup of milk. None for the daughter. Mother welcomes the son from school with tea with milk. Daughter complains, “Mother, you did not put milk in my tea.” “No, daughter. We must attend to your brother’s needs.”

I ask Mothi Mary, middle-class, educated, raised in an English-speaking Christian family, “Where does the story come from?” “I was the daughter,” she replies. I am incredulous. What is the name of this problem? It is not patriarchy, men ruling women. This is a woman disadvantaging her own daughter. How can we teach to counteract this injustice?

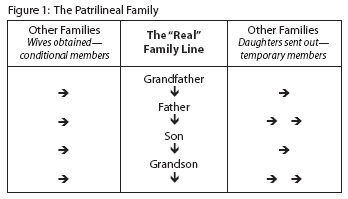

A traditional family

Sometimes, preachers say they will teach a biblical view of the family. There are problems with that. Most of the marriages that we know anything of in the Old Testament were polygamous. Are they our model? Does it matter? In fact, it does. Many were polygamous because of the deeply entrenched notion of the need for inheritance according to the law of primogeniture and patrilineal inheritance—the belief in higher status for sons that Mothi Mary’s mother shared and the view that property should pass intact to the oldest son, or at least to sons and not to daughters.

This belief still influences the thinking of many cultures in East Asia, South Asia, Africa, West Asia, and of immigrants from these places into the Western world. Indeed, the West is not so far from this thinking. Only two hundred years ago in England, in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, five daughters could not inherit their father’s property, which was “entailed” to a male cousin, and the mother and five girls all accepted this. Readers in North and South America may consider how recently and by which groups a focus on a male inheritance was (or is still?) practiced in their society.

While teaching in South Asia, I sometimes ask a class of Christians to help list on the whiteboard from their culture,...

Click here to subscribe